Calls of the void

Why Clark Ashton Smith and Algernon Blackwood would make poor camping buddies

Breach the Upside Down. Choose the blue pill. Go boldly where no man has gone before. Hop down the rabbit hole.

The fantasy of exploring a world beyond our own is a timeless one. The great minds have struggled deeply with the mysterious “out there.” As Hamlet gravely confessed to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern:

O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and

count myself a king of infinite space, were it not

that I have bad dreams.1

At some point, each of us has dreamt of just getting up and pissing off. We’d do it, too, if we could tame our anxiety about not knowing what’s next.

There are countless literary fantasies about escape—geographical and spiritual—to ponder. The ones about venturing blindly into another dimension often concern self-liberation. The two stories I cover here travel the same road but head in opposite directions: one toward wonder, and the other, terror.

During the Great Depression and for most of his life, California writer Clark Ashton Smith lived largely alone in a cabin near his parents in the Sierra foothills.2 Faced with few prospects beyond subsistence farming, odd jobs, and some editing work, he struggled with illness and the financial challenges of supporting his parents. His fantastical prose stories suggest he thought a lot about leaving everything behind.

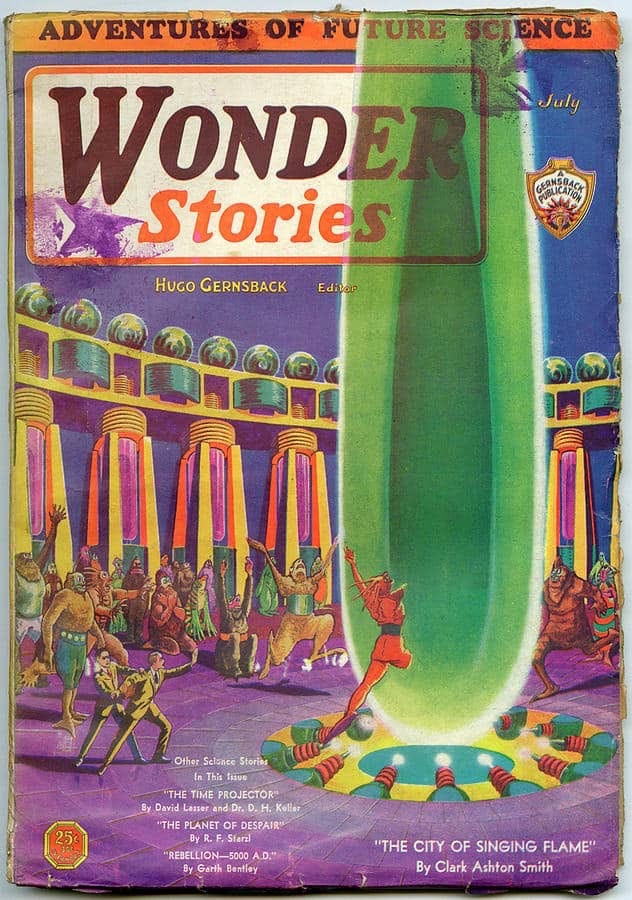

He found literary outlets for escape, thankfully. From 1929 to 1937, he published frequently in pulp magazines.3

“The City of the Singing Flame” from Wonder Stories (July 1931) is a short marvel. It takes the form of a writer’s left-behind account of discovering a “transdimensional” realm. This secret world “co-exists” with the desert High Sierras in a space “invisible and impalpable to human senses.” The writer discovers a portal to this parallel world and ventures in and out, again and again. While inside, he eventually finds and follows an eclectic group of aliens, who’ve presumably arrived there from different corners of the galaxy. They are all walking the same path now. Many are lured into sacrificing themselves to a column of fire burning at the city’s center. Smith writes:

The jet of pure, incandescent flame was mounting steadily as we entered, and it sang with the white ardor and ecstasy of a star alone in space. Again, with ineffable tones, it told me the rapture of a moth-like death in its lofty soaring, the exultation and triumph of a momentary union with its elemental essence.

Smith’s general attitude about this fantastic other world is colored by wonder and awe. His writer feels the pull of sacrifice, as if burning up would achieve the ideal of cosmic transcendence. Self-immolation might lead to something divine, a “superhuman freedom,” something more. At the very least, it would be a death less ordinary. The writer struggles to resist, but how long will he hold out?

When read aloud, Smith’s prose fiction style sounds old-fashioned, lyrical, and unsparingly earnest. It conjures a spell.

As editor S.T. Joshi points out in his biographical introduction to The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies (2014), Smith’s lofty tone was intentional. Smith was a poet first—he gained early-career notoriety as one—and a fiction writer, reluctantly, second. He wrote “Singing Flame” and other short stories because a mentor persuaded him to, and because they were easier to sell than poems.

Still, Smith’s poetic sensibility stamped everything he wrote. Joshi points to a letter where the author waxed to an admiring pen pal, H.P. Lovecraft:

My own conscious ideal has been to delude the reader into accepting an impossibility, or series of impossibilities, by means of a sort of verbal black magic, in the achievement of which I make use of prose-rhythm, metaphor, simile, tone-color, counter-point, and other stylistic resources, like a sort of incantation.

Smith’s epic voice echoes that of other fantastic writers, like Lovecraft (everything Cthulhu) and Algernon Blackwood (his wilderness stories). But where Smith gleaned a glimmer of hope from the cosmic, at least in “Singing Flame,” his contemporaries often distilled pure terror.

Take Blackwood’s “The Willows” (1907), which Lovecraft admired. The suspenseful tale is about two canoers forced to spend two nights on a mysterious river island. The trees and the enveloping darkness move strangely. One of the canoers senses the presence of an all-powerful force. But unlike the writer in “Singing Flame,” he doesn’t feel remotely drawn to it. He just feels the repulsive terror of being too close:

“All my life … I have been strangely, vividly conscious of another region—not far removed from our own world in one sense, yet wholly different in kind—where great things go on unceasingly, where immense and terrible personalities hurry by, intent on vast purposes compared to which early affairs, the rise and fall of nations, the destinies of empires, the fate of armies and continents, are all dust in the balance; vast purposes, I mean, that deal directly with the soul, and not indirectly with mere expressions of the soul——”

In these two stories, what interests me is the divergent attitudes Smith and Blackwood show toward the unknown. Smith’s writer is afraid of its fatal potential yet still drawn to it. He wants to study it. To understand it. Maybe become part of it, despite mortal danger. Blackwood’s canoer is also fearful but, conversely, repulsed by the mere thought of being amid this cosmos. He wants to flee from the island as soon as possible. Its nothingness is too sinister to behold.

I have a friend whose attitude toward the unknown is different than mine.

She once described being a missionary, working on an Indian reservation somewhere in the desert West. She and a companion were driving a lonely road through a pitch-black night. For some reason, they stopped the car and got out. Their headlights went black. Surrounding her on all sides, for the first time in her life, was pure quiet and total darkness. She described feeling chilled to the bone by the ordeal.

Today, she describes herself as a city girl.

I once traveled a road like hers, but in the opposite direction. My future wife and I were driving to a friend’s party at a country farmhouse somewhere deep in nighttime Minnesota. Our destination was at the end of a long gravel road. We parked with the rest of the late-arriving cars, maybe a quarter mile away, on the grassy slope of a ditch. Our headlights went black. We exited the car. The air was frosty. Our feet crunched over gravel as we stepped, hand in hand, toward the faint sound of a cover band warming up.

And then we just … stopped. Our eyes adjusted to the dark. Overhead, the Milky Way spilled luminously over and into the black. The memory of that sensation, being under the Infinite for the first time, still warms my soul.

In the belly of the void, my friend feared death. I felt alive.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet, https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/hamlet/read/?q=bounded%20in#line-2.2.273.

I gratefully and liberally summarize from S.T. Joshi’s biographical introduction to The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies (2014), a collection of Smith’s prose stories and poetry published by Penguin Classics.

More credit to S.T. Joshi. Ibid.