Can a screen adaptation be too good? Yes, he sighs.

On 'Ripley,' Patricia Highsmith, Disney, and how to properly scare Ichabod Crane

Movies and TV series made from great books or classic short stories are starting to bug me. Faithful or loose, adaptations possess the power to displace my memory of the source material. As a reader first and viewer second, I don’t like this dynamic.

Recently, my problem is Ripley (2024) on Netflix. It’s not that this cold-blooded take on Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) isn’t wonderful. From its icy performances to its contemporaneous approach to cinematography—a black-and-white, wide-angle aesthetic that turns aging Italian architecture into a living crypt—the show obviously is wonderful. It’s that the adaptation is too good, making me forget entirely the experience of reading Highsmith’s source novel, which I finished just two months ago.

Yes, I’m criticizing Ripley for being great. But I think it’s reasonable to demand an adaptation should complement the source and never erase it. And the more I witness Andrew Scott’s on-screen Ripley pull the strings of his victim’s friends and family, the less I remember how Highsmith’s puppeteered my sympathies for a killer while she patiently told her tale.

I dread finishing the Netflix series—which I probably will—because I risk losing the sense of my first read altogether. Sure, I can pick up the book again but its ability to shock me won’t be there anymore. With Ripley, a perfect adaptation, I’ll have seen too much.

I’ve always been a bit of a prick about screen adaptations. Ask me if I prefer the book or the movie, and I’ll reliably complain that they’re just different things. They’re not apples and oranges, both fruits that complement one other in a story salad; they’re rather coffee and beer, two beverages that have absolutely no business being on the same narrative bar.

Why are books and movies so different? The two mediums share so little when it comes to form and how they are experienced. A book is made of paper, ink, and words. To make it live, a reader must invest hours of close attention and an actively engaged imagination. As such, a book becomes a singular medium where each reader visualizes a personal version into being.

A motion picture story, on the other hand, is a fully wrought spectacle. What illuminates and sings on screen takes a witnessing mind on a fully conceived ride. To view a show is not to imagine it, really; it’s to be pulled into it. That difference between consuming print and screen—imagining versus witnessing, internally processing the words of a story versus externally absorbing light and sound—is important when considering adaptations. Do you prefer to make sense of words in your head, or take in readymade senses from a screen?

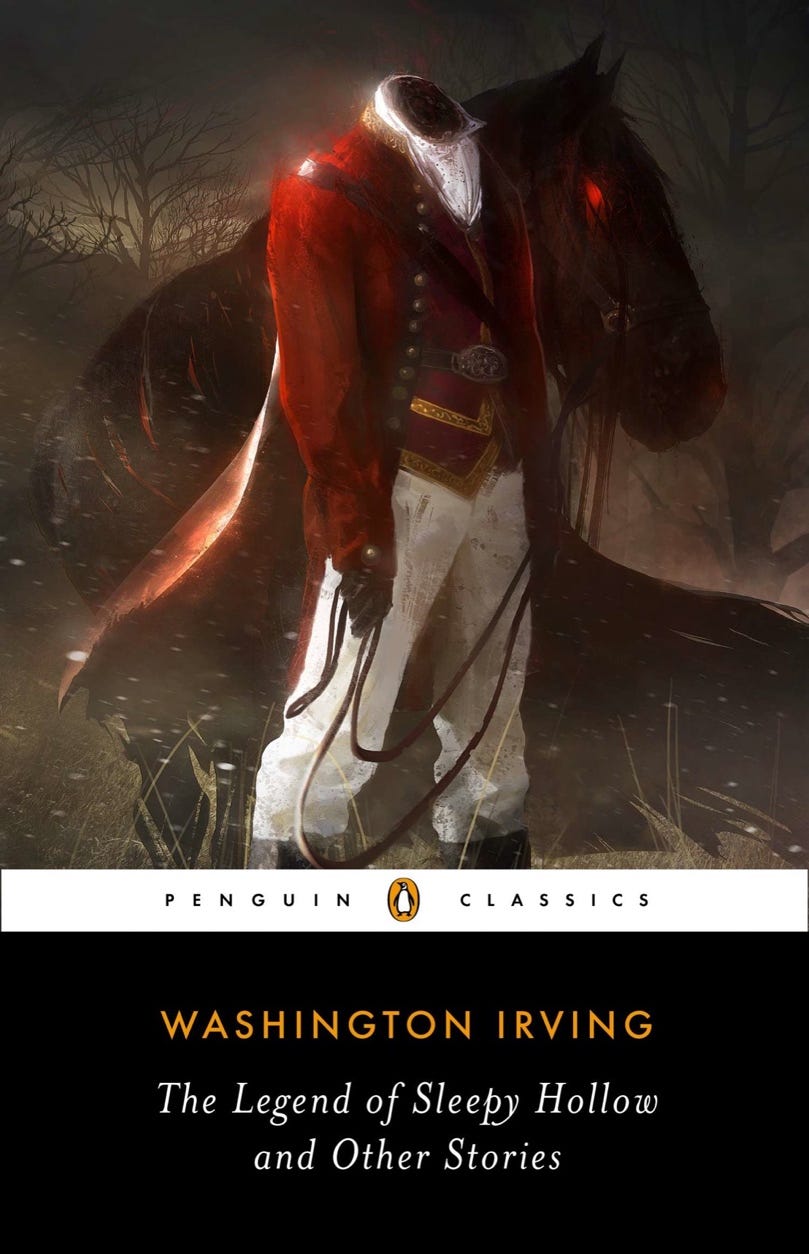

I decided to put my bookish bias to the test by looking at another story that was less faithfully adapted than The Talented Mr. Ripley: Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820).

Before reading the short story again, I had probably read it four or five times, sporadically over decades. I remembered almost nothing of its literary detail. Similarly, I’ve scattered viewings of a few screen adaptations over that time, too. I remember one of them vividly: the Disney adaptation that apparently formed the back half of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949).

If you’ve seen this screen version, you might recall that dashing sequence of the Headless Horseman on a dark horse galloping after a Ichabod Crane, who was holding on desperately to his bumbling Gunpowder. Remember when the villain kept slicing his sword at the hero’s ducking head, over and over again, and just barely missing, over and over again? The sword had become my abiding memory of Irving’s story.

And you know what? As tense as that masterful Disney scene was, it was unnecessarily unfaithful to Irving. There was no sword in the original short story. That on-screen detail was a liberty taken by animators. Sure, Disney has always embellished its sources to heighten tension. In this case, however, the embellishment was too much. Why? Irving’s original key detail was better.

In the short story, at the moment when Ichabod gets his first good look at his “midnight companion,” he beholds the true horror he’s up against. Irving paints a vivid picture:

On mounting a rising ground, which brought the figure of his fellow traveler in relief against the sky, gigantic in height, and muffled in a cloak, Ichabod was horror struck, on perceiving he was headless! but his horror was still more increased, on observing, that the head, which should have rested on his shoulders, was carried before him on the pommel of the saddle!

The head on the saddle isn’t just a showy detail, either. Ichabod guides Gunpowder over a rickety bridge that marked the end of the Headless Horseman’s rumored range. Ichabod thinks he’s safe, looks back, hoping to see his pursuer “vanish, according to rule, in a flash of fire and brimstone.” But he sees something much worse coming his way:

Just then he saw the goblin rising in his stirrups, and in the very act of hurling his head at him. Ichabod endeavoured to dodge the horrible missile, but too late. It encountered his cranium with a tremendous crash—he was tumbled headlong into the dust, and Gunpowder, the black steed, and the goblin rider, passed by like a whirlwind.

Whether you believe Irving’s head is mightier than Disney’s sword, as I do, is a matter of taste. What concerns me more is that I had lost Irving to a stirring on-screen adaptation. I hadn’t remembered the author’s legend accurately at all.

Dare I risk losing my head for Highsmith’s classic by watching the remaining three episodes of Ripley? I know I’ll finish and begrudgingly love the series … but damn it all if I won’t read Highsmith’s novel again and love the source a bit more.

Alex is always so insightful in his musings.