Actually, it isn’t what it is

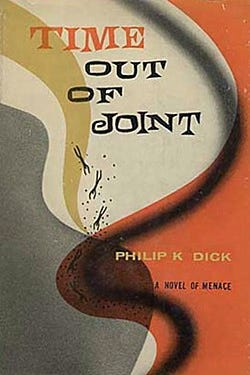

On Philip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint (1959) and Bombing the GRE

I am drawn to altered realities. Their cousins, constructed realities, I find irresistible. One of the most referenced is The Truman Show (1998), a movie about a man who slowly discovers he’s the star of the grandest reality show of all time. There’s also The Matrix mythology, which I’ve written about before, and its spiritual forerunner, The Wizard of Oz (1900, the novel; 1939, the movie).

But there are better, less referenced movies like Pleasantville (1998), where people are trapped inside a 1950s TV show, and my favorite, Synecdoche, New York (2008), where a playwright constructs and directs his own reality inside an abandoned warehouse.

What’s compelling about these worlds is the urge to believe in their driving deception: that a world made just for me is better than one that just exists for us all.

I recently finished Philip K. Dick’s novel Time Out of Joint (1959). This cautionary tale from the American master of caution is like The Truman Show in its premise: a man suspects that his life and town are constructed just for him. That everyone around him is in on a grand con for some grander reason.

Time Out of Joint tells the story of Ragle Gumm, a gifted man who’s famous for winning a newspaper contest every day. He’s admired for his success. Townspeople seem invested in him winning again and again. They accept that he doesn’t have a regular job and just wins newspaper contests for a living. But … why?

Ragle has come to suspect the course and purpose of his life are not of his own making. That the contest, his fame, his neighbors, the town, his affair with the woman next door – all the disparate parts of his life fit together too perfectly. There must be a hidden purpose behind it all.

In one great early scene, he takes his neighbor’s wife to the beach. He probably shouldn’t be taking time away from the newspaper contest, but he seems to be getting away with it. Until he’s not. Now straying from his path, Ragle’s world begins to literally crumble away. He goes in search of a refreshment stand, where:

The soft-drink stand fell into bits. Molecules. He saw the molecules, colorless, without qualities, that made it up. Then he saw through, into the space beyond it, he saw the hill behind, the trees and sky. He saw the soft-drink stand go out of existence, along with the counter man, the cash register, the big dispenser of orange drink, the taps for Coke and root beer, the ice-chests of bottles, the hot dog broiler, the jars of mustard, the shelves of cones, the row of heavy round metal lids under which were the different ice creams.

In its place was a slip of paper. He reached out his hand and took hold of the slip of paper. On it was printing, block letters.

SOFT-DRINK STAND

What’s happening? Is Ragle cracking, or is it reality? Did he make a wrong turn somewhere?

His suspicions grow. He begins paying closer attention to his life’s details. Why does everyone know his name? Why does a phone book unearthed from the town’s “ruins” contain phone numbers that don’t work? Why does a magazine contain a story about an ultra-famous movie star named Marilyn Monroe, whom he’s never heard of? On a bus ride home, did his brother-in-law really discover that the other passengers weren’t real? That they were dummies?

I’ll leave the explanation for what’s happening to Ragle for you to find out.

If you’re a PKD fan, like me, I’ll just say what you might suspect: Dick was onto something about the personal allure of a constructed reality. We all seem to maintain our own. To some extent, we are prone to believe we are the center our own universe. That each of us, somehow, can succeed at taming the world’s untamable forces by just being true to ourselves. That we have agency. That what do really matters in the grander scheme of things. That each of us is a hero, not a supporting player.

As the playwright in Synecdoche, New York more aptly puts it, “There are millions of people in the world. And none of those people is an extra. They are all leads in their own stories.”

Thus, we believe that being successful in what we do, being firm in what we believe, makes a vital difference to society at large. Believing we are important, we work to maintain sanity. We each self-construct a version of reality that’s dependent on us doing the right thing. Living a chosen, purposeful life. We are faithful to our personal narrative. If we hold fast to this illusion of “going somewhere,” we can temper life’s larger, more sinister truth: that reality isn’t linear. It doesn’t follow a single person’s story. Reality doesn’t care about the finer details of what each of us perceive as fate. For each of us, in fact, there is always another way … but only if we take time to really see it.

Dick, in many of his stories, works to peel back the veneer of reality to see what perception is made of. Over and over again, the author asks, How are we going to react when the curtain of reality is pulled back? What happens when one of us learns that the path isn’t fixed?

The closest I came to living in a constructed reality was during grad school, though I didn’t recognize it at the time. I lived in Eugene, Oregon, from 1999 to 2001. I was studying English lit. Because my apartment was near campus, a grocery store, and coffee shops, I rarely ventured too far away. Apartment to campus and back to apartment, this was my daily circle of life.

Consequently, I paid extremely close attention to my life’s details. My surroundings. My habits. And all strange things going on. (Spending ten hours of day doing close-readings of classic texts will do that to a guy.)

During my first fall quarter in that very cloudy, wet city, my car sat neglected in a same parking spot outside my apartment building for weeks. It sat unmoved for so long, in fact, that moss began growing up the tires and into its brake lights. When I finally moved my car to a different parking spot, I looked back at the original parking spot. A ring of moss had grown around my car’s perimeter on the blacktop, like a chalk outline of a dead body.

This observation was alien to my past. I thought about the moss a lot. Did it belong to my world? Was I living in the right world? Was the moss behaving as it should?

The following fall, my fateful day to take the GRE subject exam arrived. A decent exam score was a precondition for me continuing my pursuit of a Ph.D. and three more years of grad school. I needed to do well. I needed to be prepared.

I dreaded that day. I hadn’t studied for the exam. I knew I had to, but there was no time. I was supposed to read and remember a hundred classics on top of already reading and remembering dozens of others for my course work. I was, and still am, a slow reader. I wasn’t able to complete the extra reading, much less remember the few bits of knowledge I had already picked up that would come in handy. My mind just couldn’t keep pace with the conditions of my desired Ph.D. reality. Time was out of joint.

On exam day, I bolted out of my apartment’s automatic locking door at the last possible minute, rushed down four flights of stairs, and hurried to the exam room on campus. Within minutes of the exam beginning, I knew I was toast. Its questions were baffling. My answers were nonexistent.

For the next couple hours, I confronted a reality I had always feared: on the pages of the exam was my future Ph.D. slipping away. I desperately wanted to stay in my constructed reality for a few more years and earn that big degree, but I didn’t know enough. I couldn’t read the map and stay the course.

With each new and increasingly impossible question, I knew my grad school world was dying prematurely. I realized I would spend the next few months getting a conciliatory master’s degree. The realization, for someone who had been Ph.D. obsessed for a long time, was a bummer. The future I envisioned had dissolved. Time was slipping away.

At the exam’s end, I didn’t want to go back to my apartment but there was nowhere else to go. I had so much studying to do for my courses. I walked back up my building’s four flights of stairs, reached into my jacket pocket for my keys to unlock the door, but my keys weren’t there. I had forgotten to take them with me to the exam.

Still, I felt the need to get back into my apartment. To just carry on. In a vestibule outside my apartment door, I noticed a tiny door at floor level. I’d never noticed that tiny door before. It was big enough for me to squeeze through if I could open it. The door was not a regular door, however. It had no knob. It was sealed shut with two large flathead screws.

I walked down the four flights of stairs and to the apartment manager’s office. He was mysteriously sitting there, smoking, seemingly waiting. I didn’t ask to be let in to my apartment; I asked to borrow a flathead screwdriver. He recognized me and handed over a screwdriver without question.

I walked back up the stairs and screwed open the tiny door. A minute later, I had squeezed myself back inside my apartment through the darkness of a closet. I discovered my lost keys on a bookshelf.

The door I opened back to my life was smaller than I wanted it to be. I had only noticed it because I had been shocked into looking for a new way forward. I spent the next few months quietly completing my master’s and planning to move away from Oregon.

Since that episode, I’ve thought a lot about that tiny door. It helped me escape a reality that I had constructed for myself that didn’t, it turned out, fit. The tiny door led me to a new, unexpected reality, where experience was less centered around what I knew. I’ve come to accept this new reality just fine.

I think Dick would agree that anybody’s place in time is a construct of perception. Our conscious hold on our reality is dependent on how fixed our view is, and how malleable it can be when challenged.

During most moments of our lives, our self-constructed world will hold still because we’re not forced to alter our grip. We don’t notice that the soda fountain doesn’t offer what we want, because we don’t know yet to want for something else. We don’t notice that plants in the parking lot struggle to live and thrive regardless of place or circumstance, just as we do, because we don’t set aside time to observe them. We don’t realize that there is always another door to our future if we choose to look ahead … but maybe in a different direction.

There is always another way, ego be damned.

What’s most interesting about the exploration of a constructed reality – fictional or otherwise – is not how it keeps us contained; it’s how we find new freedoms when we finally unfasten the fictions holding us in place.

Another insightful and fascinating essay by Alexandyr.